por Álvaro André Zeini Cruz

1937. A noite da vibrante Shanghai estremece sob um bombardeio. Tung Kwok-man (Kenny Bee) — um compositor que faz bico de palhaço — se abriga debaixo de uma ponte, assim como Shu (Sylvia Chang), uma dançarina de cabaré. Protegem-se e, diante da iminente bifurcação dos destinos (Tung partirá para a guerra), prometem-se sobreviver, ainda que, naquele instante, estejam cercados pelo inferno pictórico de um vermelho artificialmente ardente. O maneirismo da cor anuncia a reconstrução deformada, porque se dá a partir de destroços, que Tsui Hark dirige no reencontro anos depois, quando ambos se reencatam sem se reconhecerem.

É nessa Shanghai labiríntica e pulsante que Hark opera encontros e desencontros, num espaço reerguido aos trancos e barrancos. É uma Shanghai de retalhos vivos, mas com movimentos disformes que propiciam os maus entendidos e as gags. A cena que vai acrescentando personagens incógnitos dentro de um apartamento é a síntese da mise en scène de esconde-esconde onde todos se veem, mas ninguém se enxerga.

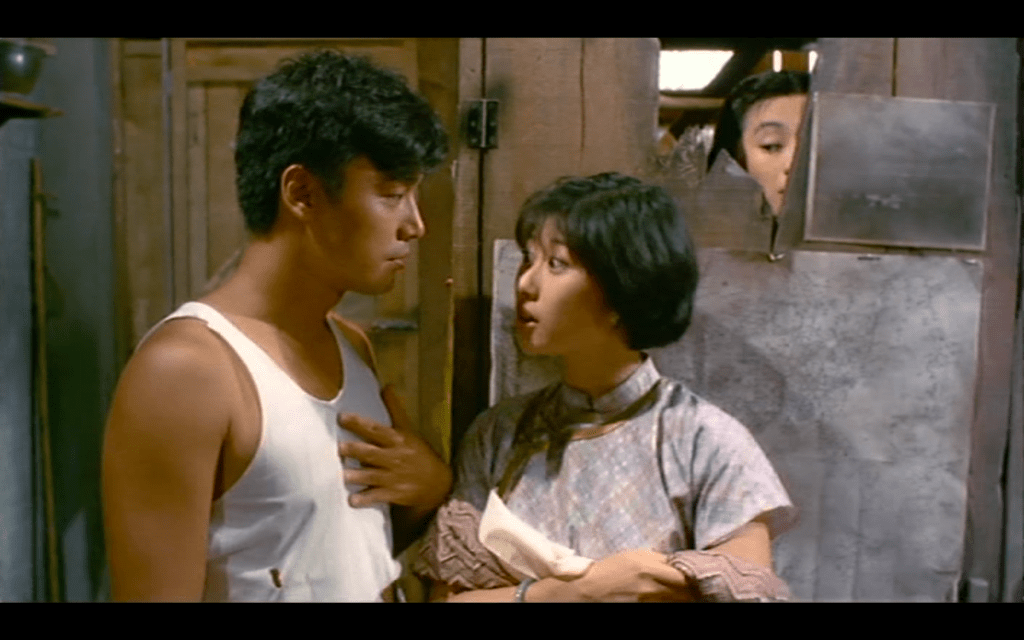

A cena começa quando Tung — também conhecido como do Do-Ré-Mi — convence Shu a subir até seu apartamento para arranjar-lhe roupas secas, depois de terem sido apanhados pela chuva. Shu titubeia, mas aceita a oferta. Nenhum deles suspeita que há um Ladrão dentro do apartamento, porque, assim que entram, o sujeito consegue se esgueirar para outro cômodo, separado por uma porta de tábuas mal ajambradas. Mas Shu precisa se trocar, e para dar privacidade a ela, Tung segue para o esconderijo do Ladrão, que, no típico timing de uma fração de segundo, se enfia dentro de um barril. Tung e Shu demoram alguns instantes até notarem que, naquela casa de escombros bricolados, não há privacidade, já que há sempre uma janela, uma fresta ou um buraco à espreita. Dão de cara um com o outro e, desconcertados, correm em convergência; na gag de comédia romântica, tromba-se seminus.

Inicia-se um intrincado jogo de gato e rato, sem que os gatos tenham ciência da quantidade de ratos que há ali, ou que está por vir. Isso porque logo chega a vez de Shu se esconder: ela não quer ser flagrada pela melhor amiga, Stool (Sally Yeh), também apaixonada por Tung (e a situação se torna mais suspeita agora que Shu veste uma camisa dele). Mas Stool é insistente e não basta a Shu manter-se incógnita atrás das paredes; ela se esconde num cômodo-armário, enquanto Stool pula a janela, obrigando o Ladrão — que se escondia sob o parapeito — encontrar outro esconderijo. Agora é Shu quem se esconde, mas observa, com caras e bocas, as outras duas pontas do triângulo pela abertura proporcionada por uma tábua quebrada.

Batidas na porta fazem com que Stool também se esconda; temendo que seja Shu, ela vai para o mesmo armário onde a própria Shu está. As roupas nos cabides — corroboradas pelo pacto com a verossimilhança da farsa — impedem que elas se vejam, uma circunstância improvável sob um realismo rigoroso, mas característica dessa comédia romântica farsesca-marxista; não por conta do velho Karl, mas pelos irmãos homônimos, dados a esse tipo de estripulia cênica (assim como Keaton, Lloyd e Chaplin). Quem chega é o Professor, cujo corpo camufla o Ladrão (antes atrás da porta), que, por sua vez, se esgueira para seu último e mais estapafúrdio esconderijo — uma bacia (penico?), que o sujeito segura ridiculamente sobre a cabeça.

A situação finalmente termina quando o Professor vê Shu pelo buraco e, ao dizer “ladrão, saia!”, revela não a moça, mas o próprio Ladrão a suas costas, sob o penico. É Stool quem, então, sai do armário, e do triângulo amoroso, passamos a um quadrilátero financeiro: Do-Ré-Mi anuncia que o Ladrão de óculos escuros foi quem roubou o dinheiro dela, mas o Professor recém-chegado foi quem o gastou. O Ladrão — o único que tudo viu — anuncia “mais confusão por vir” e revela Shu, sobrepondo o conflito de ordem prática por outro mais complicado — o romântico. O corte rente a um espirro de Shu revela as duas amigas estremecidas, mas Stool, a rival apaixonada, será essencial no desenlace da trama, quando reenlaça esse amor alheio, sobrevivente ao apagamento dos rostos, teimoso em se reencontrar através de identidades mais profundas. Comédia romântica delirante que, entre a farsa e a tragédia, faz rir e palpitar, não nessa ordem, mas pela mise en scène de um caos recalculado.

Shanghai Blues

by Álvaro André Zeini Cruz

1937. The night of vibrant Shanghai trembles under a bombing raid. Tung Kwok-man (Kenny Bee)—a composer who moonlights as a clown—takes shelter under a bridge, as does Shu (Sylvia Chang), a cabaret dancer. They protect each other and, facing the imminent parting of their paths (Tung will leave for war), promise to survive, even as they are surrounded in that moment by the pictorial hell of an artificially burning red. The mannerism of the color announces a deformed reconstruction—built from rubble—that Tsui Hark orchestrates in their reunion years later, when they fall for each other again without recognizing one another.

It is in this labyrinthine, pulsing Shanghai that Hark stages meetings and missed connections, in a space rebuilt haphazardly. It is a Shanghai of living fragments, but with disjointed movements that foster misunderstandings and gags. The scene that gradually adds unknown characters inside an apartment is the synthesis of a hide-and-seek mise-en-scène where everyone is seen, yet no one truly sees.

The scene begins when Tung—also known as Do-Re-Mi—convinces Shu to go up to his apartment to get dry clothes after they are caught in the rain. Shu hesitates but accepts the offer. Neither suspects that there is a Thief inside the apartment, for as soon as they enter, the man manages to slip into another room, separated by a door of loosely fitted planks. But Shu needs to change clothes, and to give her privacy, Tung moves into the Thief’s hiding spot, who, in classic split-second timing, ducks inside a barrel. Tung and Shu take a moment to realize that, in this cobbled-together house of rubble, there is no privacy, for there is always a window, a crack, or a hole lying in wait. They come face-to-face and, flustered, run in convergence; in the romantic comedy gag, they collide half-naked.

An intricate game of cat and mouse begins, though the cats are unaware of how many mice are present—or yet to arrive. That’s because it’s soon Shu’s turn to hide: she doesn’t want to be caught by her best friend, Stool (Sally Yeh), who is also in love with Tung (and the situation grows more suspicious now that Shu is wearing his shirt). But Stool is persistent, and simply staying hidden behind walls isn’t enough for Shu; she hides in a closet-room, while Stool jumps through the window, forcing the Thief—who was hiding under the windowsill—to find another hiding spot. Now it’s Shu who hides, but she watches, with expressions and gestures, the other two points of the triangle through a gap provided by a broken plank.

Knocks at the door force Stool to hide as well; fearing it might be Shu, she goes into the same closet where Shu already is. The clothes on the hangers—supported by the farce’s pact with plausibility—prevent them from seeing each other, an improbable circumstance under strict realism but characteristic of this farcical-Marxist romantic comedy—not because of old Karl, but the eponymous brothers, known for this kind of stage mischief (as were Keaton, Lloyd, and Chaplin). The one who arrives is the Professor, whose body conceals the Thief (previously behind the door), who in turn sneaks into his final and most absurd hiding place—a basin (chamber pot?), which the man ridiculously holds over his head.

The situation finally ends when the Professor sees Shu through the hole and, upon shouting “thief, come out!”, reveals not the girl but the Thief himself behind him, under the chamber pot. It is Stool who then emerges from the closet, and from the love triangle, we move to a financial quadrilateral: Do-Re-Mi announces that the Thief in sunglasses was the one who stole her money, but the newly arrived Professor was the one who spent it. The Thief—the only one who saw everything—declares “more confusion to come” and reveals Shu, layering the practical conflict with a more complicated one—the romantic. A cut to one of Shu’s sneezes reveals the two friends startled, but Stool, the lovestruck rival, will be essential in the plot’s resolution, when she reconnects this love that belongs to others—a love that survives the erasure of faces, stubbornly seeking to reunite through deeper identities. A delirious romantic comedy that, between farce and tragedy, makes us laugh and ache, not in that order, but through the mise-en-scène of recalculated chaos.