por Álvaro André Zeini Cruz

So, goodbye, my dear, dear world of a father.

Episódio 9, 4ª temporada. Do altar, as palavras de Shiv (Sarah Snook), dispensadas ao caixão do pai, badalam dor e libertação. Ecoam das abóbodas de “Igreja e Estado” a “De olhos abertos”, episódio final de Succession, quando assumem a forma dessa promessa que intitula o episódio.

Corta para:

427 a. C. “Édipo Rei”. Abandonado ainda bebê, Édipo desconhece a predição que o separou dos pais biológicos — o Rei Laio e a Rainha Jocasta. As peripécias da tragédia, no entanto, fazem com que o destino prenunciado se cumpra e, ignorante de sua origem, Édipo mata o pai e desposa a mãe. A descoberta tardia do parricídio e a do incesto desenlaça a tragédia com a imposição das autopenitencias: Jocasta se suicida e Édipo arranca os próprios olhos; cego, proíbe retroativamente o desejo pela mãe. A tragédia engendra desejos e proibições, pulsões e privações que serão basilares para a psicanálise pouco mais de dois milênios depois.

Corta para:

1924. Freud usa Édipo para conjecturar um dos fundamentos da psicanálise; a tragédia é realocada para exemplificar uma operação psicológica inconsciente que, para o pai da psicanálise, todo ser humano vive na infância. O Complexo de Édipo estrutura desejo, rivalidade, proibição e recalque na triangulação entre pai, mãe e filho; segundo Freud, o desejo (inconsciente) da criança pela mãe ou pelo pai desencadeia uma rivalidade com a outra parte parental, que, quando superada — em processos que envolvem admiração e identificação — compõe o dispositivo de controle das pulsões (o superego) e a lapidação da personalidade (o ego). Mas Freud avança nas tragédias e localiza Hamlet como um herdeiro de Édipo, traçando diferenciações entre personalidades e contextos históricos. Se em Édipo, “a fantasia infantil desejosa que subjaz ao texto é abertamente exposta e realizada como ocorreria em um sonho”, em Hamlet, “ela permanece recalcada; […] só ficamos cientes de sua existência através de consequências inibidoras”[1]. Para Freud, o destino trágico em Hamlet é postergado pelo titubear do herói, que revive o complexo sob a tônica da admiração por aquele que desposa a mãe Gertrudes — o tio Cláudio, que assassinara o irmão pelo trono.

Corta para:

28/05/2023. Episódio 10, 4ª temporada: “De olhos abertos”. O episódio começa com Shiv e Kendall (Jeremy Strong) contando os votos que definirão a venda (ou não) da Waystar Royco; percebem que Roman (Kieran Culkin) pode definir o futuro da empresa. Na dianteira, Shiv se espanta ao encontrar o irmão na casa da mãe Caroline (Harriet Walter) com o supercílio suturado (no episódio anterior, Roman acabara atropelado pela “plebe” ao descer da torre). Essa mãe — que em outra ocasião disse que não deveria tê-los tido — admite sua incapacidade de cuidar dos olhos do filho; ela alega ter aflição de olhos, esses “face eggs” responsáveis pelo sentido mais suscetível ao conglomerado midiático que faz dos Roy bilionários. É um comentário que pode parecer um detalhe, não fosse Roman um jovem Édipo em estado constante de penitência.

Roman talvez seja a chave para tentar elucidar os olhares deste series finale. Isso porque ele é um Édipo com complexo de Édipo: preso na fase fálica (e compulsivo em enviar fotos do próprio pênis), ele compensa a falta materna pela relação-prótese que tem com Gerri (J. Smith-Cameron) e vive uma retroalimentação entre o sadismo desajustado e a espera das repressões humilhantes, que dão a ele um prazer inacabado. Com a triangulação incompleta (as representações maternas são apenas circunstanciais), resta a Roman permanecer nesse lugar que esbarra na devoção ao pai, sem que isso ultrapasse à fase de latência, isto é, a dissolução do Complexo de Édipo, quando a personalidade é reajustada para ir além da relação parental. Dos filhos de Logan Roy (Brian Cox), Roman é visivelmente o mais imaturo, o menos propício à vida social, algo que se desdobra do flerte com o fascismo ao atropelamento que faz com que ele quase perca a visão (e perderia, se dependesse da mãe). Então, surge Hamlet.

Hamlet é Kendall, aquele que, segundo Freud, é o Édipo revisitado, não tanto pela luz no desejo ou na penitência, mas pelo recalque que se consolida como hesitação. Ainda que Succession não explicite, Kendall aparenta ser maníaco-depressivo, o que colabora para que ele hesite em romper com o Rei (ou vingar-se dele), a não ser quando, como em Hamlet, isso se dá em rompantes. Esses impulsos, porém, logo abrandam, seja nas conciliações narrativas, seja nas crises de consciência que Kendall (como Hamlet) tem — o episódio em que ele se desespera à procura do presente dado pelos filhos demonstra a consciência de que ele “não é melhor do que o pecador a quem deve punir” (e cito Freud sobre Hamlet).

Retirados na casa materna — mas com a mãe como ausência quase completa —, Roman, Kendall e Shiv suspendem o histórico de rivalidades e traições para realizarem um ritual de “cura”: uma regressão que restaura a infância em duplo sentido, já que, na cena na cozinha (cômodo-coração dos espaços domésticos), há uma harmonia não constada nos relatos que sempre tivemos da infância original. Nessa brincadeira, Kendall parece-lhes, enfim, um rei possível, porque aparece como um monarca lúdico, imaginado por essa infância revivida e curada, afastando-se de ser uma réplica mal-acabada do pai que está morto (mas só como corpo e só por este instante). Isso porque o fim da reinação consagra o novo rei com uma ironia: para merecer a coroa, Kendall precisa tomar uma taça “envenenada”. Então, ele é coroado com o próprio veneno. A brincadeira acaba nesta que, como revelado pelos produtores, foi a última cena da série a ser gravada (cura pelo menos aos atores). Mas o episódio continua. De volta à casa do pai, os irmãos assistem uma gravação de Logan também num momento de brincadeiras, cercado dos seus (e Connor, o primogênito constantemente excluído, é o único com o pai). De lá, voltam à torre do castelo. Ao escritório.

Na sala do pai, Roman é o primeiro a hesitar; Kendall, então, dá o abraço que abre os pontos na sobrancelha do irmão. O sangue marca a ameaça de uma nova cegueira a esse Édipo reconhecível a olho nu, de tão raso. A cena termina com uma articulação de imagens — uma escultura (um elmo), uma gravura (Shakespeare?), uma capa de revista (Logan). Na sala de reuniões, é a vez de Shiv vacilar na encenação dos olhares, que desviam de Kendall e tentam ver a face oculta (o corte reaberto) de Roman. A hesitação se torna epifania quando Kendall evoca a memória do pai, desvelando a si próprio como farsa (que vem depois da tragédia), boneco inflado pelo fel entranhado pelo pai ao longo dos anos, cópia volátil (e volúvel) que não ressuscita nem restaura o patriarca original, que, bem ou mal, servia de ponte entre eles e o mundo. Hamlet aqui é simulacro de um símbolo e flutua neste mundo de imagens desenraizadas.

Na última sala — todas elas com paredes de vidro para que tudo seja visto —, Shiv constata a farsa: Kendall não é Logan, mas uma continuidade fajuta, inábil em garanti-los porque é incapaz de sustentar mentira ou verdade. Todavia, não se pode negar ser um homem de seu tempo: Kendall distorce os fatos, acreditando que basta só ele crer (Shiv caçoa quando Kendall diz ser o mais velho; Roman já havia dito que sem foto não há fato). Roman, então, questiona a continuidade em sua forma mais prosaica ao lembrar que as crianças de Kendall não são filhos biológicos do irmão. Lembrança que abre uma brecha: ao contrário de Logan, Kendall não é luz, sombra ou sangue desses filhos. É nada, uma outra ausência que se abre sobre a nova geração. Diante dessa verdade, ele enfia os dedos nos olhos de Roman. Hamlet tenta cegar Édipo. É seu arroubo final na tentativa de ser rei.

Shiv é quem traz o já bastante comentado desfecho de Rei Lear: Tom (Matthew Macfadyen), o marido que ela nunca amou, herda o reino, tal qual Albany, o genro bajulador da tragédia de Shakespeare. Ao trair os irmãos em favor desse homem que despreza, Shiv faz um sacrifício complexo: numa primeira leitura, ela — constantemente subjugada por ser mulher — compactua com a abertura de um novo patriarcado, com o qual terá maior poder de barganha; além de estar submetido a Mattson (Alexander Skarsgård), Tom é urdido por Shiv entre desejos, recalques e retaliações. Contudo, uma segunda leitura é possível: ao romper o legado de Logan, ela conduz e acompanha as sobras paternas a seus devidos destinos — a morte e purificação do símbolo-pai, o exílio dela e dos irmãos. Nesse sentido, é Goneril (porque se sacrifica, ainda que simbolicamente), mas também Antígona, filha de Édipo, aquela que conduz o pai até a morte, até libertá-lo, cumprindo a promessa que fizera diante do caixão — So, goodbye, my dear, dear world of a father.

A última aparição de Roman é num super close-up expressionista, porque deforma o rosto e compõe um monstro-humano de olhar baixo; ele encara o chão, essa fina crosta que, nas tragédias, não necessariamente nos separa do inferno. Na saída de Shiv, é a mão de Tom que se abre monstruosamente; uma garra sobre esse trono costurado em couro e contra-plongée, como se viesse de “Cosmópolis” (de Cronenberg). Shiv olha pela janela para buscar horizontes (e estômago), ainda que no subterrâneo de seu arranha-céu. Mas está de olhos abertos. Kendall, por fim, senta-se sob o lusco-fusco, diante do oceano; enquanto encara esse manancial de símbolos e sonhos, é filmado de perfil, um meio homem, esquálido, vazio, incapaz de cumprir a “citação” shakespeariana preferida do pai: “take the fucking money”.

É sob a luz do entardecer, sufocado pela trilha incidental e pela agitação da água, de tudo, que esse Hamlet de espuma encerra Succession sob uma tragédia destes tempos, o destino incontornável de ser uma imagem vazia.

Freud tinha razão: cada época tem o Édipo (ou o Hamlet) que lhe cabe. Ser. Ou não ser.

…

[1] “Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939

A interpretação dos sonhos [recurso eletrônico] / Sigmund Freud; tradução Walderedo Ismael de Oliveira. – [20. ed.]. – Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 2018.”

Trecho de: Sigmund Freud. “A interpretação dos sonhos”. Apple Books.

Oedipus, Hamlet, and Antigone

by Álvaro André Zeini Cruz

So, goodbye, my dear, dear world of a father.

Episode 9, Season 4. From the altar, the words of Shiv (Sarah Snook), delivered to her father’s coffin, ring with pain and liberation. They echo from the vaults of “Church and State” to “With Open Eyes,” the final episode of Succession, when they take the form of that promise which titles the episode.

Cut to:

427 BC. Oedipus Rex. Abandoned as a baby, Oedipus is unaware of the prophecy that separated him from his biological parents—King Laius and Queen Jocasta. The twists of tragedy, however, cause the foretold destiny to be fulfilled, and, ignorant of his origin, Oedipus kills his father and marries his mother. The late discovery of the patricide and of the incest unravels the tragedy with the imposition of self-punishments: Jocasta commits suicide and Oedipus gouges out his own eyes; blind, he retroactively prohibits the desire for his mother. The tragedy engenders desires and prohibitions, drives and deprivations that will become fundamental for psychoanalysis a little over two millennia later.

Cut to:

1924. Freud uses Oedipus to conjecture one of the foundations of psychoanalysis; the tragedy is relocated to exemplify an unconscious psychological operation that, for the father of psychoanalysis, every human being experiences in childhood. The Oedipus Complex structures desire, rivalry, prohibition, and repression in the triangulation between father, mother, and child; according to Freud, the (unconscious) desire of the child for the mother or father triggers a rivalry with the other parental part, which, when overcome—in processes involving admiration and identification—composes the device for controlling drives (the superego) and the honing of personality (the ego). But Freud advances through tragedies and locates Hamlet as an heir of Oedipus, tracing differences between personalities and historical contexts. If in Oedipus, “the underlying wishful fantasy of childhood is openly displayed and realized as it would be in a dream,” in Hamlet, “it remains repressed; […] we only become aware of its existence through its inhibiting consequences”[1]. For Freud, the tragic fate in Hamlet is postponed by the hero’s hesitation, who relives the complex under the tone of admiration for the one who married his mother Gertrude—the uncle Claudius, who murdered his brother for the throne.

Cut to:

05/28/2023. Episode 10, Season 4: “With Open Eyes.” The episode begins with Shiv and Kendall (Jeremy Strong) counting the votes that will decide the sale (or not) of Waystar Royco; they realize Roman (Kieran Culkin) may define the company’s future. In the lead, Shiv is surprised to find her brother at their mother Caroline’s (Harriet Walter) house with his eyebrow sutured (in the previous episode, Roman ended up being trampled by the “rabble” after descending from the tower). This mother—who on another occasion said she shouldn’t have had them—admits her inability to care for her son’s eyes; she claims to have a dread of eyes, those “face eggs” responsible for the sense most susceptible to the media conglomerate that made the Roys billionaires. It’s a comment that may seem like a detail, were it not for Roman being a young Oedipus in a constant state of penance.

Roman may be the key to trying to elucidate the gazes in this series finale. This is because he is an Oedipus with an Oedipus complex: stuck in the phallic stage (and compulsive about sending pictures of his own penis), he compensates for the maternal lack through the prosthetic relationship he has with Gerri (J. Smith-Cameron) and lives a feedback loop between maladjusted sadism and the wait for humiliating repressions, which give him an unfinished pleasure. With the triangulation incomplete (the maternal representations are only circumstantial), Roman remains in this place that bumps into devotion to the father, without surpassing the latency stage, that is, the dissolution of the Oedipus Complex, when the personality is readjusted to go beyond the parental relationship. Of Logan Roy’s (Brian Cox) children, Roman is visibly the most immature, the least suited for social life, something that unfolds from flirting with fascism to the trampling that almost costs him his sight (and would have, if it depended on his mother). Then, Hamlet appears.

Hamlet is Kendall, the one who, according to Freud, is Oedipus revisited, not so much in the light of desire or penance, but in the repression that solidifies as hesitation. Although Succession doesn’t make it explicit, Kendall appears to be manic-depressive, which contributes to his hesitation in breaking with the King (or avenging him), except when, as in Hamlet, it happens in outbursts. These impulses, however, soon subside, whether in narrative reconciliations or in the crises of conscience that Kendall (like Hamlet) has—the episode in which he desperately searches for the gift from his children demonstrates the awareness that he “is no better than the sinner he is to punish” (and I quote Freud on Hamlet).

Secluded in the maternal house—but with the mother as an almost complete absence—Roman, Kendall, and Shiv suspend their history of rivalries and betrayals to perform a “healing” ritual: a regression that restores childhood in a double sense, since, in the kitchen scene (the heart-room of domestic spaces), there is a harmony not found in the accounts we have always had of their original childhood. In this play, Kendall finally seems to them a possible king, because he appears as a playful monarch, imagined by this revived and healed childhood, moving away from being a botched replica of the father who is dead (but only as a body and only for this moment). This is because the end of the reign consecrates the new king with an irony: to deserve the crown, Kendall must drink a “poisoned” chalice. So, he is crowned with his own poison. The play ends here, which, as revealed by the producers, was the last scene of the series to be filmed (a healing at least for the actors). But the episode continues. Back at the father’s house, the siblings watch a recording of Logan also in a moment of play, surrounded by his own (and Connor, the constantly excluded firstborn, is the only one with the father). From there, they return to the castle tower. To the office.

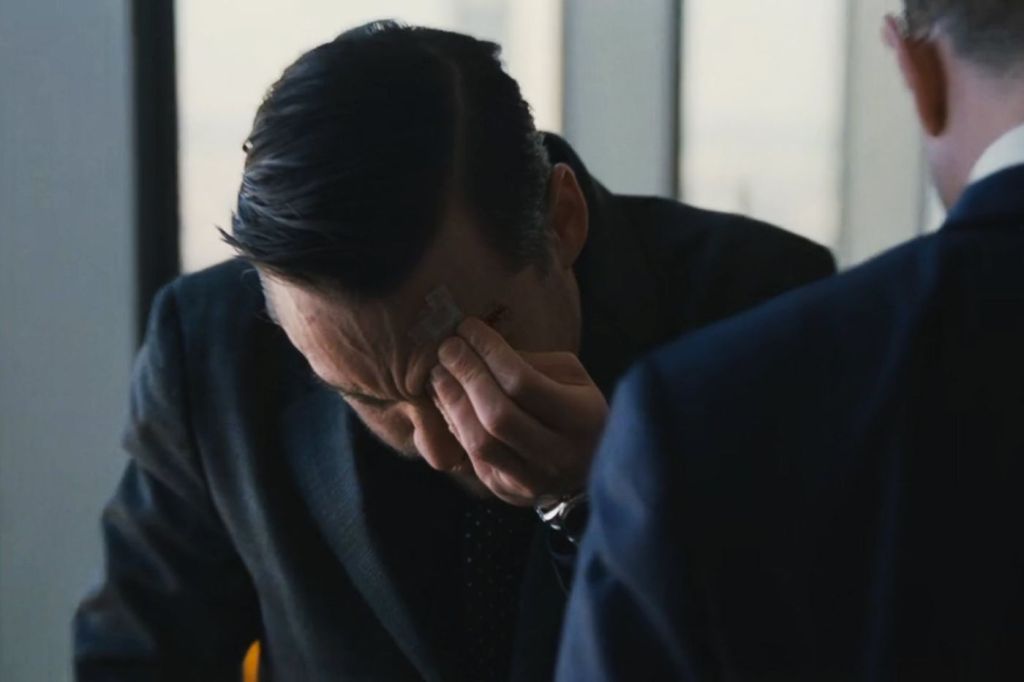

In the father’s room, Roman is the first to hesitate; Kendall then gives the hug that opens the stitches on his brother’s eyebrow. The blood marks the threat of a new blindness for this Oedipus, recognizable to the naked eye, so shallow. The scene ends with a montage of images—a sculpture (a helmet), an engraving (Shakespeare?), a magazine cover (Logan). In the boardroom, it’s Shiv’s turn to falter in the enactment of gazes, which avert from Kendall and try to see the hidden side (the reopened cut) of Roman. The hesitation becomes an epiphany when Kendall evokes the memory of the father, revealing himself as a farce (which comes after the tragedy), a puppet inflated by the bile ingrained by the father over the years, a volatile (and fickle) copy that neither resurrects nor restores the original patriarch, who, for better or worse, served as a bridge between them and the world. Hamlet here is a simulacrum of a symbol and floats in this world of uprooted images.

In the last room—all of them with glass walls so everything can be seen—Shiv confirms the farce: Kendall is not Logan, but a fake continuity, inept at guaranteeing them because he is incapable of sustaining either lie or truth. However, one cannot deny he is a man of his time: Kendall distorts facts, believing it’s enough that only he believes (Shiv mocks when Kendall says he is the eldest; Roman had already said that without a photo there is no fact). Roman then questions the continuity in its most prosaic form by reminding him that Kendall’s children are not his biological children. A reminder that opens a gap: unlike Logan, Kendall is not light, shadow, or blood to these children. He is nothing, another absence that opens over the new generation. Faced with this truth, he sticks his fingers in Roman’s eyes. Hamlet tries to blind Oedipus. It is his final outburst in the attempt to be king.

Shiv is the one who brings the already much-commented ending of King Lear: Tom (Matthew Macfadyen), the husband she never loved, inherits the kingdom, much like Albany, the fawning son-in-law in Shakespeare’s tragedy. By betraying her brothers in favor of this man she despises, Shiv makes a complex sacrifice: in a first reading, she—constantly subjugated for being a woman—colludes with the opening of a new patriarchy, with which she will have greater bargaining power; besides being subject to Matsson (Alexander Skarsgård), Tom is woven by Shiv among desires, repressions, and retaliations. However, a second reading is possible: by breaking Logan’s legacy, she leads and accompanies the paternal remnants to their rightful destinations—the death and purification of the father-symbol, the exile of her and her brothers. In this sense, she is Goneril (because she sacrifices herself, even if symbolically), but also Antigone, daughter of Oedipus, the one who leads the father to his death, until she frees him, fulfilling the promise she made before the coffin—So, goodbye, my dear, dear world of a father.

Roman’s last appearance is in an expressionist super close-up, because it distorts the face and composes a human-monster with a downcast gaze; he stares at the ground, that thin crust that, in tragedies, does not necessarily separate us from hell. At Shiv’s exit, it is Tom’s hand that opens monstrously; a claw over this throne stitched in leather and shot in low angle, as if coming from Cosmopolis (by Cronenberg). Shiv looks out the window to seek horizons (and stomach), even if in the subterranean level of her skyscraper. But she has her eyes open. Kendall, finally, sits in the twilight, before the ocean; while staring at this wellspring of symbols and dreams, he is filmed in profile, a half-man, gaunt, empty, incapable of fulfilling his father’s favorite Shakespeare “quote”: “take the fucking money.”

It is under the light of dusk, suffocated by the incidental score and the agitation of the water, of everything, that this foam Hamlet concludes Succession under a tragedy of these times, the inescapable fate of being an empty image.

Freud was right: every era has the Oedipus (or the Hamlet) it deserves. To be. Or not to be.

….

[1] “Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939

A interpretação dos sonhos [recurso eletrônico] / Sigmund Freud; tradução Walderedo Ismael de Oliveira. – [20. ed.]. – Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 2018.”

Excerpt from: Sigmund Freud. “A interpretação dos sonhos”. Apple Books.